Learn how to digitally sign software artifacts to ensure a safer chain of custody that can be traced back to the source. The article is for anyone new to Sigstore and its sub-projects. It starts by teaching you the basics such as: “What is Software Supply Chain Security?” and defines key terms and concepts like SLSA and SBOM. By the end, you’ll have learnt how to set up your own Sigstore Rekor server with hands-on labs and code examples.

Table of Contents

- Chapter 1. Introducing Sigstore

- Overview

- Learning Objectives

- What is Software Supply Chain Security?

- Key Software Supply Chain Security Concepts and Terms

- The Motivation and History of the Sigstore Project

- The Sigstore Architecture: Cosign, Fulcio, and Rekor

- Further Reading Resources

- Chapter 2. Cosign: Container Signing, Verification, and Storage in an OCI Registry

- Overview

- Learning Objectives

- Code Signing with Cosign

- Cosign in Practice

- Keyless Signing

- Installing Cosign with Homebrew or Linuxbrew

- Installing Cosign with Linux Package Managers

- Installing Cosign with Go

- Installing Cosign with the Cosign Binary

- Signing a Container with Cosign

- Generating a Cosign Key Pair

- Creating a Container

- Building and Running a Container

- Publishing a Container to a Registry

- Signing a Container and Pushing the Signature to a Registry

- Verify a Container’s Signature

- Adding an Additional Signature

- Signing Blobs and Standard Files with Cosign

- Signing an SBOM with Cosign

- Further Reading Resources

- Chapter 3. Fulcio: A New Kind of Root Certificate Authority For Code Signing

- Overview

- Learning Objectives

- Certificates

- Certificate Authority

- OpenID Connect (OIDC) Tokens

- How Fulcio Issues Certificates

- The Purpose and Contributions of Fulcio

- Lab

- Generating a Fulcio Certificate

- Inspecting and Verifying Fulcio Certificates

- Further Reading Resources

- Chapter 4. Rekor: Software Supply Chain Transparency Log

- Overview

- Learning Objectives

- Transparency Log

- Public Instance of Rekor

- Rekor Usage

- Setting Up an Internal Rekor Instance

- Lab

- Rekor Installation

- Querying Rekor

- Signing and Uploading Metadata with rekor-cli

- Install Your Own Rekor Instance Locally (Optional)

- Create and Run a Database Backend

- Install and Set Up Trillian

- Install Rekor Server

- Test Rekor

- Further Reading Resources

- Chapter 5. Sigstore: Using the Tools and Getting Involved with the Community

- Overview

- Learning Objectives

- A Short History Leading to Sigstore

- Getting Involved with the Community

- Resources for Learning More

- Lab

- Sign up for GitHub

- Create a GitHub Repository

- Create a Local Directory for the Repository

- Create Django Container Files

- Steps to Automate Keyless Signing

- Create GitHub Actions File

- Generate GitHub Personal Access Token

- Initialize Git Repository and Push Changes

- Confirm Keyless Signing via GitHub Actions

- Verify Signatures

- Further Reading Resources

Chapter 1. Introducing Sigstore

Overview

Compromises in the software supply chain have been on the rise over the past decade. Attackers have, for instance, distributed compilers with backdoors added (as in the XcodeGhost compromise), broken into software build systems to inject malicious code (as in the SolarWinds attack), and hijacked automatic update systems to distribute malware. The count of publicly reported software supply chain compromises, depending on the methodology, numbers in the hundreds or thousands. See the figure below for a graph describing the growth of software supply chain attacks.

Figure 1. Count of Software Supply Chain Attacks by Year Reported

Countering these compromises through prevention, mitigation, and remediation has therefore taken on increasing urgency. Founded in 2020, the Open Source Security Foundation (OpenSSF) has begun to devise improved defenses against software supply chain attacks. As a cross-industry collaboration, the OpenSSF partners with private companies, government agencies, and individuals to support their mission of proactively handling security. The Sigstore project is one of these improved defenses, providing a method for guaranteeing the end-to-end integrity of software artifacts.

This chapter defines software supply chain security and provides examples of attacks on the software supply chain. You’ll become acquainted with several concepts and terms associated with software supply chain security. Finally, we’ll dive into the motivation and history of the Sigstore project and an overview of the technical architecture.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Define software supply chain security.

- Have an understanding of key software supply chain security concepts and terms.

- Discuss the motivation and history of the Sigstore project.

- Explain the overall architecture of the Sigstore project.

What is Software Supply Chain Security?

It can be all too easy to label all software issues as supply chain security issues. One might think: All security issues have to be introduced somewhere in the software’s supply chain or how else would these vulnerabilities end up in the finished software? But software supply chain security has a narrower, technical meaning: security issues introduced by the third-party components and technologies used to write, build, and distribute software. A generic example can help illustrate the difference. Imagine ACME company unintentionally creates a SQL injection vulnerability in a piece of software that ACME company distributes. This is not a software supply chain security issue. Code from ACME’s own developers is responsible for this security issue. But should ACME company use an open source software component that has been maliciously tampered with to send sensitive secrets to an attacker when the code was built, then ACME would be the victim of a software supply chain attack. In that case, the supply chain of ACME’s developers is the origin of the security issue.

Software supply chain compromises can involve both malicious and unintentional vulnerabilities. The insertion of malicious code anywhere along the supply chain poses a severe risk to downstream users, but unintentional vulnerabilities in the software supply chain can also lead to risks should some party choose to exploit these vulnerabilities. For instance, the log4j open source software vulnerability in late 2021 exemplifies the danger of vulnerabilities in the supply chain, including the open source software supply chain. In this case, log4j, a popular open source Java logging library, had a severe and relatively easily exploitable security bug. Many of the companies and individuals using software built with log4j found themselves vulnerable because of this bug.

Malicious attacks, or what often amounts to code tampering, deserve special recognition though. In these attacks, an attacker controls the functionality inserted into the software supply chain and can often target attacks on specific victims. These attacks often prey on the lack of integrity in the software supply chain, taking advantage of the trust that software developers place in the components and tools they use to build software. Notable attack vectors include compromises of source code systems, such as GitHub or GitLab; build systems, like Jenkins or Tekton; and publishing infrastructure attacks on either corporate software publishing servers, update servers, or on community package infrastructure. Another important attack vector is when an attacker steals the credentials of an individual open source software developer and adds malicious code to a source code management system or published package.

Sigstore aims to help restore this missing integrity, ensuring that software developers and downstream consumers can verify and trust the software on which they depend.

Key Software Supply Chain Security Concepts and Terms

There are a number of concepts and terms that software professionals interested in software supply chain security use frequently. Not only are these terms generally useful, but these concepts are also relevant to Sigstore and the Sigstore project’s mission.

SLSA Framework

The Supply chain Levels for Software Artifacts (SLSA, pronounced “salsa”) framework is an incremental series of measures that protect the integrity of a software project’s software supply chain. There are four SLSA levels (1-4) with higher levels representing more security. The incremental approach allows organizations to adopt SLSA in a piecemeal fashion. The security measures associated with SLSA span the source code, build system, provenance, and any associated computer systems. The SLSA framework is itself an open source project.

Software Integrity

Software artifacts that have integrity have not been modified in an unauthorized manner. For instance, an artifact that has been replaced by an attacker or an artifact that has had bit flips due to hard drive corruption would not have integrity.

Code Signing

Code signing refers to the creation of a cryptographic digital signature that ties an identity (often a company or a person) to an artifact. This signature proves to the consumer that the software has not been tampered with and that the specified party approves the artifact. Signing an artifact typically requires generating a keypair of public and private keys. The signer uses the private key to digitally sign the artifact and the consumer uses the public key to verify that the private key was used to sign the artifact.

Attestations

An attestation is signed metadata about one or more software artifacts. Metadata can refer, for instance, to how an artifact was produced, including the build command and associated dependencies. In fact, there are many different types of possible metadata for a software artifact. Crucially, an attestation must also include a signature by the party that created the attestation. The SLSA project contains more information on the definition of a software attestation.

SBOMs

SBOM (pronounced “S-bomb”) refers to a software bill of materials, or a list of ingredients that make up software components. SBOMs are widely viewed as one helpful building block for software security and software supply chain security risk management. You can find more information on SBOMs via a Linux Foundation SBOM report.

Provenance

In the context of software security, provenance refers to information about who produced one or more software artifacts, and what steps and materials were used to produce those artifacts. This information helps software consumers make informed decisions about what software to consume and trust. You can find a specific technical definition of provenance via the SLSA website.

*Throughout this course, we’ll use these terms frequently, so you will become more familiar with their usage and applications.

The Motivation and History of the Sigstore Project

Neither software supply chain security, software integrity, nor code signing are new topics. For instance, a 1984 Turing award lecture by Kenneth Thompson, entitled “Reflections on Trusting Trust,” arguably defined the modern debate over software supply chain security.

But despite a decades-long interest in software integrity, the practice of signing and verifying software artifacts remains relatively rare. In open source package managers that support package signatures, relatively few maintainers use existing methods to sign released artifacts. One 2016 study of the Python Package Index ecosystem found that a mere four percent of projects had signatures and that less than one-tenth of one percent of users downloaded these signatures for verification. The story is similar in many other software packaging ecosystems.

Moreover, traditional methods for signing software packages suffer from at least two defects. First, the software consumer must know what public key to use to verify the artifact. Traditional methods make finding this information cumbersome. Second, a single signature conveys relatively little information: that some party created that artifact. But it would be preferable to be able to convey more information, or metadata, about the software so that consumers can make more informed decisions about what software to use.

Sigstore aims to change this modern state of affairs. Several organizations including Google, Red Hat, Purdue University, and others began working together under the aegis of the Open Source Security Foundation (OpenSSF) in late 2020 and early 2021 to build the Sigstore project. Sigstore aims to make code signing and verification simple, widespread, and part of the invisible digital infrastructure that most computer users have become accustomed to when they, for instance, surf the web and benefit from widespread web traffic encryption.

To effect this change, Sigstore implements an architecture with multiple components that together enable a streamlined signing and verification process for software developers and consumers. Moreover, Sigstore uses additional technologies beyond a signing tool to bind identities such as emails to public keys and a transparency log to store software artifact metadata. These technologies will be explained in the next section.

The Sigstore Architecture: Cosign, Fulcio, and Rekor

Sigstore’s GitHub repository contains a number of projects, although three are arguably central to the overall project and enable the technical vision described previously.

- Cosign creates a key pair with public and private keys and then uses the private key to create a digital signature of software artifacts, that is, any item produced during the software development lifecycle, such as containers or open source software packages. This is the first step in creating a system that supports end-to-end integrity of a software artifact: the software developer must attach a signature to the created artifact. And, unlike previous approaches, Cosign (in combination with Fulcio, described next) reduces the burden on software developers by allowing them to use their identity associated with popular internet platforms (like GitHub) and therefore avoid storing private keys, which is both a hassle and a security risk.

- Fulcio is a certificate authority that binds public keys to email addresses (such as a Google account) using OpenID Connect. Fulcio serves as a trusted third party, helping parties that need to attest and verify identities. By connecting an identity to a verified email or other unique identifier, developers can attest that they truly did create their signed artifacts and later software consumers can verify that the software artifacts they use really did come from the expected software developers.

- Rekor stores records of artifact metadata, providing transparency for signatures and therefore helping the open source software community monitor and detect any tampering of the software supply chain. On a technical level, it is an append-only (sometimes called “immutable”) data log that stores signed metadata about a software artifact, allowing software consumers to verify that a software artifact is what it claims to be.

The image below provides a diagram describing the system architecture of Sigstore.

Figure 2. System Architecture of Sigstore

Together, these components provide a system that makes widespread signing and verification of software artifacts possible. Software developers can more easily sign what they create, and software consumers can ensure that their software possesses integrity and was not compromised by tampering.

Further Reading Resources

For Good Measure – Counting Broken Links: A Quant’s View of Software Supply Chain Security

Novel Malware XcodeGhost Modifies Xcode, Infects Apple iOS Apps and Hits App Store

Cybersecurity: Federal Response to SolarWinds and Microsoft Exchange Incidents

Open Source Security Foundation (OpenSSF)

Sigstore

The ‘most serious’ security breach ever is unfolding right now. Here’s what you need to know.

SLSA

Linux Foundation SBOM Report

Reflections on Trusting Trust

Diplomat: Using Delegations to Protect Community Repositories

Cosign

Fulcio

Rekor

Chapter 2. Cosign: Container Signing, Verification, and Storage in an OCI Registry

Overview

This chapter will focus on Cosign, which supports software artifact signing, verification, and storage in an OCI (Open Container Initiative) registry. While Cosign was developed with containers and container-related artifacts in mind, it can also be used for open source software packages and other file types. Cosign can therefore be used to sign blobs (binary large objects), files like READMEs, SBOMs (software bill of materials), Kubernetes Helm Charts, Tekton bundles (an OCI artifact containing Tekton CI/CD resources like tasks), and more.

By signing software, you can authenticate that you are who you say you are, which can in turn enable a trust root so that developers who leverage your software and consumers who use your software can verify that you created the software artifact that you have said you’ve created. They can also ensure that that artifact was not tampered with by a third party. As someone who may use software libraries, containers, or other artifacts as part of your development lifecycle, a signed artifact can give you greater assurance that the code or container you are incorporating is from a trusted source.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Explain what Cosign is.

- Install Cosign.

- Sign several software artifacts.

- Verify that software artifacts have been signed.

- Have an understanding of the trust root around Sigstore.

Code Signing with Cosign

Software artifacts are distributed widely, can be incorporated into the software of other individuals and organizations, and are often updated throughout their life spans. End users and developers who build upon existing software are increasingly aware of the possibility of threats and vulnerabilities in packages, containers, and other artifacts. How can users and developers decide whether to use software created by others? One answer that has been increasingly gaining traction is code signing.

While code signing is not new technology, the growing prevalence of software in our everyday lives coupled with a rising number of attacks like SolarWinds and Codecov has created a more pressing need for solutions that build trust, prevent forgery and tampering, and ultimately lead to a more secure software supply chain. Similar in concept to a signature on a document that was signed in the presence of a notary or other professional who can certify your identity, a signature on a software artifact attests that you are who you say you are and that the code was not altered. Instead of a recognized notary when you sign software, it is a recognized certificate authority (CA) that validates your identity. These checks that go through recognized bodies able to establish a developer’s identity support the root of trust that security relies on so that bad actors cannot compromise software.

Code signing involves a developer, software publisher, or entity (like an automated workload) digitally signing a software artifact to confirm their identity and ensure that the artifact was not tampered with since having been signed. Code signing has several implementations, and Cosign is one such implementation, but all code signing technology follows a similar process as Cosign.

Code Signing

A developer (or organization) looking to sign their code with Cosign will first generate a key pair with public and private keys, and will then use the private key to create a digital signature for a given software artifact. A key pair is a combination of a signing key (also known as a public key) that is used to sign data, and a verification key (also known as a private key) that is used to verify data signed with the corresponding signing key. Public keys can be known to others (and can be openly distributed), and private keys must only be known by the owner for signatures to be secure. With the key pair, the developer will sign their software artifact and store that signature in the registry (if applicable). This signature can later be verified by others through searching for an artifact, finding its signature, and then verifying it against the public key.

Cosign in Practice

We will go through the installation and use Cosign in the Lab section. To give you an understanding of Cosign commands, we’ll go over the basics here.

Once you have Cosign installed, you would be able to generate a key pair in Cosign with the following command:

$ cosign generate-key-pair

Enter password for private key:

Enter again:

Private key written to cosign.key

Public key written to cosign.pub

You can sign a container and store the signature in the registry with the cosign sign command.

$ cosign sign --key cosign.key sigstore-course/demo

Enter password for private key:

Pushing signature to:

index.docker.io/sigstore-course/demo:sha256-87ef60f558bad79beea6425a3b28989f01dd417164150ab3baab98dcbf04def8.sig

Finally, you can verify a software artifact against a public key with the cosign verify command. This command will return 0 if at least one Cosign formatted signature for the given artifact is found that matches the public key. Any valid formats are printed to standard output in a JSON format.

$ cosign verify --key cosign.pub sigstore-course/demo

The following checks were performed on these signatures:

- The cosign claims were validated

- The signatures were verified against the specified public key

{"Critical":{"Identity":{"docker-reference":""},"Image":{"Docker-manifest-digest":"sha256:87ef60f558bad79beea6425a3b28989f01dd417164150ab3baab98dcbf04def8"},"Type":"cosign container image signature"},"Optional":null}

You should now have some familiarity with the process of signing and verifying code in Cosign. In the lab portion of this chapter, we will go through installing Cosign and understanding its commands in greater detail with a full demonstration.

Code signing provides developers and others who release code a way to attest to their identity, and in turn, those who are consumers (whether end users or developers who incorporate existing code) can verify those signatures to ensure that the code is originating from where it is said to have originated, and check that that particular developer (or vendor) is trusted.

Keyless Signing

Code signing is a solution for many use cases related to attestation and verification with the goal of a more secure software supply chain. While key pairs are a technology standard that have a long history in technology (SSH keys, for instance), they create their own challenges for developers and engineering teams. The contents of a public key are very opaque; humans cannot readily discern who the owner of a given key is. Traditional public key infrastructure, or PKI, has done the work to create, manage, and distribute public-key encryption and digital certificates. A new form of PKI is keyless signing, which prevents the challenges of long-lived and opaque signing keys.

In keyless signing, short-lived certificates are generated and linked into the chain of trust through completing an identity challenge that confirms the identity of the signer. Because these keys persist only long enough for signing to take place, signature verification ensures that the certificate was valid at the time of signing. Policy enforcement is supported through an encoding of the identity information onto the certificate, allowing others to verify the identity of the developer who signed.

Through offering short-lived credentials, keyless signing can support the recommended practice of operating your build environment like a production environment, where long-lived keys can be stolen and used to sign malicious artifacts. Even if these short-lived keys used in keyless signing were stolen, they’d be useless!

While keyless signing can be used by individuals in the same manner as long-lived key pairs, it is also well suited for continuous integration and continuous deployment workloads. Keyless signing works by sending an OpenID Connect (OIDC) token to a certificate authority like Fulcio to be signed by a workload’s authenticated OIDC identity. This allows the developer to cryptographically demonstrate that the software artifact was built by the continuous integration pipeline of a given repository, for example.

Cosign uses ephemeral keys and certificates, signs them automatically by the Fulcio root certificate authority, and stores these signatures in the Rekor transparency log, which automatically provides an attestation at the time of creation.

You can manually create a keyless signature with the following command in cosign. In our example, we’ll use Docker Hub. If you would like to follow along, ensure you are logged into Docker Hub on your local machine and that you have a Docker repository with an image available. The following example assumes a username of docker-username and a repository name of demo-container.

$ COSIGN_EXPERIMENTAL=1 cosign sign docker-username/demo-container

Generating ephemeral keys...

Retrieving signed certificate...

Your browser will now be opened to:

At this point, a browser window will open and you will be directed to a page that asks you to log in with Sigstore. You can authenticate with GitHub, Google, or Microsoft. Note that the email address that is tied to these credentials will be permanently visible in the Rekor transparency log. This makes it publicly visible that you are the one who signed the given artifact, and helps others trust the given artifact. That said, it is worth keeping this in mind when choosing your authentication method. Once you log in and are authenticated, you’ll receive feedback of “Sigstore Auth Successful”, and you may now safely close the window.

On the terminal, you’ll receive output that you were successfully verified, and you’ll get confirmation that the signature was pushed.

Successfully verified SCT...

tlog entry created with index:

Pushing signature to: index.docker.io/docker-username/demo-container

…

If you followed along with Docker Hub, you can check the user interface of your repository and verify that you pushed a signature.

You can then further verify that the keyless signature was successful by using cosign verify to check.

$ COSIGN_EXPERIMENTAL=1 cosign verify docker-username/demo-container

The following checks were performed on all of these signatures:

- The cosign claims were validated

- The claims were present in the transparency log

- The signatures were integrated into the transparency log when the certificate was valid

- Any certificates were verified against the Fulcio roots.

…

{"Critical":{"Identity":{"docker-reference":""},"Image":{"Docker-manifest-digest":"sha256:97fc222cee7991b5b061d4d4afdb5f3428fcb0c9054e1690313786befa1e4e36"},"Type":"cosign container image signature"},"Optional":null}

…

As part of the JSON output, you should get feedback on the issuer that you used and the email address associated with it. For example, if you used Google as the authenticator, you will have “Issuer”:”https://accounts.google.com”,”Subject”:”[email protected]”}}] as the last part of your output.

Cosign Installation

There are a few different ways to install Cosign to your local machine or remote server. The approach you choose should be based on the way you set up packages, the tooling that you use, or the way that your organization recommends.

Installing Cosign with Homebrew or Linuxbrew

Those who are running macOS locally may be familiar with Homebrew as a package manager. There is also a Linuxbrew version for those running a Linux distribution. If you are using macOS and would like to leverage a package manager, you can review the official documentation to install Homebrew to your machine.

To install Cosign with Homebrew, run the following command.

$ brew install cosign

To update Cosign in the future, you can run brew upgrade cosign to get the newest version.

Installing Cosign with Linux Package Managers

Cosign is supported by the Arch Linux, Alpine Linux, and Nix package managers. In the releases page, you’ll also find .deb and .rpm packages for manual download and installation.

To install Cosign on Arch Linux, use the pacman package manager.

$ pacman -S cosign

If you are using Alpine Linux or an Alpine Linux image, you can add Cosign with apk.

$ apk add cosign

For NixOS, you can install Cosign with the following command:

$ nix-env -iA nixpkgs.cosign

And for NixOS Linux, you can install Cosign using nixos.cosign with the nix-env package manager.

$ nix-env -iA nixos.cosign

For Ubuntu and Debian distributions, check the releases page and download the latest .deb package. At the time of this writing, this would be version 1.8.0. To install the .deb file, run:

$ sudo dpkg -i ~/Downloads/cosign_1.8.0_amd64.deb

For CentOS and Fedora, download the latest .rpm package from the releases page and install Cosign with:

$ rpm -ivh cosign-1.8.0.x86_64.rpm

You can check to ensure that Cosign is successfully installed using the cosign version command following installation. When you run the command, you should receive output that indicates the version you have installed.

Installing Cosign with Go

You may choose to install Cosign with Go if you already are working in the programming language Go. Additionally, installing with Go will work across different distributions. First, check that you have Go installed on your machine, and ensure that it is Go version 1.16 or later.

$ go version

As long as your output indicates that you are at Go 1.16 or above, you’ll be ready to install Cosign with Go. Your output should appear similar to the following.

go version go1.17.6 darwin/arm64

If you run into an error or don’t receive output like the above, you’ll need to install Go in order to install Cosign with Go. Navigate to the official Go website in order to download the appropriate version of Go for your machine.

With Go 1.16 or above installed, you are ready to install Cosign with Go, using the following command.

$ go install github.com/sigstore/cosign/cmd/cosign@latest

The resulting binary from this installation will be placed at $GOPATH/bin/cosign.

Installing Cosign with the Cosign Binary

Installing Cosign via its binary offers you greater control over your installation, but this method also requires you to manage your installation yourself. In order to install via binary, check for the most updated version in the open source GitHub repository for Cosign under the releases page.

You can use the wget command to install the most recent binary. In our example, the release we are installing is 1.8.0.

$ wget

"https://github.com/sigstore/cosign/releases/download/v1.8.0/cosign-linux-amd64"

Next, move the Cosign binary to your bin folder.

$ mv cosign-linux-amd64 /usr/local/bin/cosign

Finally, update permissions so that Cosign can execute within your filesystem.

$ chmod +x /usr/local/bin/cosign

You’ll need to ensure that you keep Cosign up to date if you install via binary. You can always later opt to use a package manager to update Cosign in the future.

Signing a Container with Cosign

We briefly went over the commands that you would take to sign software artifacts in Cosign earlier in the chapter. Let’s step through signing a container with Cosign. We are using a container because containerized workloads were what developers had in mind when working on Sigstore. However, the steps we are taking to sign a container are very similar to the steps that we would take to sign any other software artifact that can be published in a container registry, and we will discuss signing blobs a little later.

Before beginning this section, ensure that you have Docker installed and that you are running Docker Desktop if that is relevant for your operating system. For guidance on installing and using Docker, refer to the official Docker documentation. In order to push to the Docker container registry, you will need a Docker Hub username. If you are familiar with using a different container registry, feel free to use that.

Generating a Cosign Key Pair

In order to generate a Cosign key pair, you’ll need to have Cosign installed, which you can do following the previous section.

If you have not already created a Cosign key pair, navigate to your user directory so we can create one.

$ cd ~

You’ll use Cosign to create the key pair now.

$ cosign generate-key-pair

Once you run this command, you’ll receive output asking you to create a password for the private key. It is recommended to have a password for an extra layer of security, but you can also leave this field blank, especially if you are just using this key pair for testing purposes. You’ll be prompted to enter this password twice.

Enter password for private key:

Enter again:

Once you have entered the private key password, you’ll receive feedback that the private key and public key were written.

Private key written to cosign.key

Public key written to cosign.pub

Your private key, stored in the cosign.key file, should not be shared with anyone. Your public key, stored in the cosign.pub file, will be used to identify that you are the key holder who is signing your software artifacts.

Now both of these files exist in your home user directory (don’t forget where they are!), and you can inspect them if you would like by using the cat command, as in:

$ cat cosign.pub

You’ll get output that indicates the beginning and end of your public key, with a large string of mixed-case alphanumeric values in between.

-----BEGIN PUBLIC KEY-----

…

-----END PUBLIC KEY-----

With your keys set up, you are ready to move on to creating and signing a container.

Creating a Container

With your keys set up, you’ll now be creating a new container. Create a new directory within your user directory that is the same as your Docker username and, within that, a directory called hello-container. If you will be opting to use a registry other than Docker, feel free to use the relevant username for that registry.

$ mkdir -p ~/docker-username/hello-container

Move into the directory.

$ cd ~/docker-username/hello-container

Let’s create the Dockerfile that describes the container. This will be essentially a “Hello, World” container for demonstration purposes.

Use the text editor of your choice to create the Dockerfile. You can use Visual Studio Code or a command line text editor like nano. Just ensure that the file is called exactly Dockerfile with a titlecase and no extension.

$ nano Dockerfile

Type the following into your editor:

FROM alpine

CMD ["echo", "Hello, Cosign!"]

This file is instructing the container to use the Alpine Linux distribution, which is lightweight and secure. Then, it prints a “Hello, Cosign!” message onto the command-line interface.

Once you are satisfied that your Dockerfile is the same as the text above, you can save and close the file. Now you are ready to build the container.

Building and Running a Container

Within the same hello-container directory, you can build the container. You should use the format docker-username/image-name to tag your image, since you’ll be publishing it to a registry.

$ docker build -t docker-username/hello-container .

If you receive an error message or a “failed” message, check that your user is part of the docker group and that you have the right permissions to run Docker. For testing, you may also try to run the above command with sudo.

You should get guidance in the output that your build was successful when you receive no errors.

=> => naming to docker.io/library/hello-container

At this point, your container is built and you can verify that the container is working as expected by running the container.

$ docker run hello-container

You should receive the expected output of the echo message you added to the Dockerfile.

Hello, Cosign!

You can further confirm that the Docker container is among your listed containers by listing all of your active containers.

$ docker ps -a

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

c828db494203 hello-container "echo 'Hello, Cosign…" 13 seconds ago Exited (0) 9 seconds ago confident_lamarr

Your output will be similar to the above, but the timestamps and name will be different.

Now that you have built your container and are satisfied that it is working as expected, you can publish and sign your container.

Publishing a Container to a Registry

We will be publishing our container to the Docker registry. If you are opting to use a different registry, your steps will be similar.

Access the Docker container registry at hub.docker.com and create a new repository under your username called hello-container. We will be making this public, but you can make it private if you prefer. In any case, you can delete this once you are satisfied that you have signed the container.

Once this is set up, you can push the container you created to the Docker Hub repository.

$ docker push docker-username/hello-container

You should be able to now access your published container via your Docker Hub account. Once you ensure that this is there, you are ready to push a signature to the container.

Signing a Container and Pushing the Signature to a Registry

Now that the container is in a registry (in our example, it is in Docker Hub), you are ready to sign the container and push that signature to the registry.

Make sure you are in the right directory for your Cosign key pair.

$ cd ~

From there, you will call your registry user name and container name with the following Cosign command. Note that we are signing the image in Docker Hub with our private key which is held locally in the cosign.key file.

$ cosign sign --key cosign.key docker-username/hello-container

You will be prompted for the password, even if you have left the password blank.

Enter password for private key:

Enter your password (or press ENTER if you don’t have a password), and then press ENTER.

You’ll receive output indicating that the signature was pushed to the container registry.

Pushing signature to: index.docker.io/docker-username/hello-container

In the case of Docker Hub, on the web interface there should be a SHA (secure hash algorithm) added to the tag, enabling you to confirm that your pushed signature was registered. We’ll now manually verify the signature with Cosign.

Verify a Container’s Signature

We’ll be demonstrating this on the container we just pushed to a registry, but you can also verify a signature on any other signed container using the same steps. While you will more likely be verifying signatures in workloads versus manually, it is still helpful to understand how everything works and is formatted.

Let’s use Cosign to verify that the formatted signature for the image matches the public key.

$ cosign verify --key cosign.pub docker-username/hello-container

Here, we are passing the public key contained in the cosign.pub file to the cosign verify command.

You should receive output indicating that the Cosign claims were validated.

Verification for

index.docker.io/docker-username/hello-container:latest --

The following checks were performed on each of these signatures:

- The cosign claims were validated

- The signatures were verified against the specified public key

[{"critical":{"identity":{"docker-reference":"index.docker.io/docker-username/hello-container"},"image":{"docker-manifest-digest":"sha256:690ecfd885f008330a66d08be13dc6c115a439e1cc935c04d181d7116e198f9c"},"type":"cosign container image signature"},"optional":null}]

The whole output will include JSON format which includes the digest of the container image, which is how we can be sure these detached signatures cover the correct image.

Adding an Additional Signature

If multiple people are working on the same container, or you need a team signature in addition to an individual developer signature, you can add more than one signature to a container. You’ll need to generate keys specifically for each signatory.

It may be helpful to also add the -a flag to add annotations so that others can check to verify different keys. For example, we’ll annotate this signature to state that this is the organization signature.

$ cosign sign --key other.key -a organization=signature

docker-username/hello-container

As before, the user signing will be prompted to enter their password for the key. When someone verifies the signatures on this key, they’ll receive the values entered in the annotation as part of the signed JSON payload under the optional section at the end.

… [{"critical":{"identity":{"docker-reference":"index.docker.io/docker-username/hello-container"},"image":{"docker-manifest-digest":"sha256:690ecfd885f008330a66d08be13dc6c115a439e1cc935c04d181d7116e198f9c"},"type":"cosign container image signature"},"optional":{"organization":"signature"}}]

This container now has two signatures, with one signature that has additional annotation.

Signing Blobs and Standard Files with Cosign

Cosign can sign more than just containers. Blobs, or binary large objects, and standard files can be signed in a similar way. You can publish a blob or other artifact to an OCI (Open Container Initiative) registry with Cosign.

First, we’ll create an artifact (in this case, a standard file that contains text). We’ll call the file artifact and fill it with the “hello, cosign” text.

$ echo "hello, cosign" > artifact

Cosign offers support for signing blobs with the cosign sign-blob and cosign verify-blob commands. To sign our file, we’ll pass our signing key and the name of our file to the cosign sign-blob command.

$ cosign sign-blob --key cosign.key artifact

You’ll get output similar to the following, and a prompt to enter your password for your signing key.

Using payload from: artifact

Enter password for private key:

With your password entered, you’ll receive your signature output.

MEUCIAb9Jxbbk9w8QF4/m5ADd+AvvT6pm/gp0HE6RMPp3SfOAiEAsWnpkaVZanjhQDyk5b0UPnlsMhodCcvYaGl1sj9exJI=

You will need this signature output to verify the artifact signature. Use the cosign verify-blob command and pass in the public key, the signature, and the name of your file.

$ cosign verify-blob --key cosign.pub --signature MEUCIAb9Jxbbk9w8QF4/m5ADd+AvvT6pm/gp0HE6RMPp3SfOAiEAsWnpkaVZanjhQDyk5b0UPnlsMhodCcvYaGl1sj9exJI= artifact

Note that the whole output of the signature needed to be passed to this command. You’ll get feedback that the blob’s signature was verified.

Verified OK

You can also publish the artifact to a container registry such as Docker Hub and sign the artifact’s generated image with Cosign. Running this command will create a new repository in your Docker Hub account . We will call this artifact but you can use an alternate meaningful name for you.

$ cosign upload blob -f artifact docker-username/artifact

You’ll receive feedback that the file was uploaded, and it will already have the SHA signature as part of the artifact.

Uploading file from [artifact] to [index.docker.io/docker-username/artifact:latest] with media type [text/plain] File [artifact] is available directly at [index.docker.io/v2/docker-username/artifact/blobs/sha256:dcf8ff… Uploaded image to: index.docker.io/docker-username/artifact@sha256:d10846…

Being able to sign blobs provides you with the opportunity to sign README files and scripts rather than just containers. This can ensure that every piece of a software project is accounted for through signatures and provenance.

Signing an SBOM with Cosign

Signatures are just one form of metadata, you can add other signed metadata making different assertions about a software package. For example, a software bill of materials, or SBOM, is an inventory of the components that make up a given software artifact. Increasingly, SBOMs are considered part of the foundation that makes a more secure software supply chain.

As a developer leveraging the software that others make, an SBOM can help you understand what goes into the software that you’re using. As a developer releasing software into the world, including an SBOM with what you ship can help others trust the provenance of the software. You can instill greater trust in your software products by signing your SBOMs along with other software artifacts. Let’s demonstrate how to create an SBOM and sign the SBOM using our hello-container example.

We can create an SBOM with the open source Syft tool from the Anchore community. First, to install Syft, you can review the guidance on installation on the project’s README file. They recommend installing the install script from the GitHub repository with curl. We recommend that you inspect the install.sh file prior to downloading.

$ curl -sSfL

https://raw.githubusercontent.com/anchore/syft/main/install.sh | sh -s -- -b /usr/local/bin

With Syft installed, you can generate an SBOM with the syft command.

$ syft docker-username/hello-container

You should receive output regarding all the components in your container. If you created the same container that we demonstrated above, your output should be very similar to the below.

✔ Loaded image

✔ Parsed image

✔ Cataloged packages [14 packages]

NAME VERSION TYPE

alpine-baselayout 3.2.0-r18 apk

alpine-keys 2.4-r1 apk

apk-tools 2.12.7-r3 apk

busybox 1.34.1-r5 apk

ca-certificates-bundle 20211220-r0 apk

libc-utils 0.7.2-r3 apk

libcrypto1.1 1.1.1n-r0 apk

libretls 3.3.4-r3 apk

libssl1.1 1.1.1n-r0 apk

musl 1.2.2-r7 apk

musl-utils 1.2.2-r7 apk

scanelf 1.3.3-r0 apk

ssl_client 1.34.1-r5 apk

zlib 1.2.12-r0 apk

We would like this SBOM to be output to a particular file format that we can sign with Cosign. We’ll use the Linux Foundation Project SPDX format, which stands for Software Package Data Exchange. SPDX is an open standard for communicating SBOM information.

We’ll output this to a file called latest.spdx to represent the most recent container version’s SBOM. You may want to version SBOMs along with your releases, but keeping a most up-to-date “latest” version can generally be helpful.

$ syft docker-username/hello-container:latest -o spdx > latest.spdx

You’ll get output similar to the SBOM output again (without the list of all the components).

✔ Loaded image

✔ Parsed image

✔ Cataloged packages [14 packages]

With the file written, you can inspect it.

$ cat latest.spdx

This will be a fairly lengthy file, even for our small container image. It will provide information for each of the components that make up the software in the hello-container image.

SPDXVersion: SPDX-2.2

DataLicense: CC0-1.0

SPDXID: SPDXRef-DOCUMENT

DocumentName: docker-username/hello-container-latest

…

##### Package: zlib

PackageName: zlib

SPDXID: SPDXRef-Package-apk-zlib-7934e949300925b1

PackageVersion: 1.2.12-r0

PackageDownloadLocation: NOASSERTION

FilesAnalyzed: false

PackageLicenseConcluded: Zlib

PackageLicenseDeclared: Zlib

PackageCopyrightText: NOASSERTION

ExternalRef: SECURITY cpe23Type cpe:2.3:a:zlib:zlib:1.2.12-r0:*:*:*:*:*:*:*

ExternalRef: PACKAGE_MANAGER purl pkg:alpine/[email protected]?arch=aarch64&upstream=zlib&distro=alpine-3.15.4

Next, you’ll attach the SBOM via Cosign to the container that you have hosted on Docker Hub or other container registry.

$ cosign attach sbom --sbom latest.spdx

docker-username/hello-container:latest

You’ll receive feedback once the SBOM is pushed to the container registry.

…

Uploading SBOM file for [index.docker.io/docker-username/hello-container:latest] to [index.docker.io/docker-username/hello-container:sha256-690ecfd885f008330a66d08be13dc6c115a439e1cc935c04d181d7116e198f9c.sbom] with mediaType [text/spdx].

Though you have pushed the SBOM with Cosign, you haven’t signed the SBOM. Depending on your organization’s approach to security, an SBOM and a signed container may be adequate. You will sign the SBOM in a similar way to signing other software artifacts.

Make sure you are in the correct local directory for your Cosign key pair. If you generated the key pair in the signed container example, it will be in your home user directory, so make sure you move your present working directory there with the cd ~ command.

You’ll be signing the SBOM with the SHA that you received in the output from the previous command. This is a long string that starts with sha256 and ends with .sbom. You can verify that this was pushed to the container registry by checking the web user interface of Docker Hub or alternate registry.

$ cosign sign --key cosign.key docker-username/hello-container:sha256-690ecfd885f008330a66d08be13dc6c115a439e1cc935c04d181d7116e198f9c.sbom

Again, you’ll be prompted for the password for your Cosign private key. Once you enter the password, you’ll receive output that the signature was pushed to the registry.

Pushing signature to: index.docker.io/docker-username/hello-container

You can verify the signature on the SBOM as you can with any other signature.

$ cosign verify --key cosign.pub docker-username/hello-container:sha256-690ecfd885f008330a66d08be13dc6c115a439e1cc935c04d181d7116e198f9c.sbom

As before, you’ll receive output that the SBOM’s signature is verified and you’ll receive a JSON formatted digest of the information. You have now created and signed an SBOM for your container!

Further Reading Resources

Docker Hub

Linuxbrew

Visual Studio Code

Chapter 3. Fulcio: A New Kind of Root Certificate Authority For Code Signing

Overview

Previous chapters explained the overall architecture of Sigstore and how Sigstore allows users to authenticate artifacts against identities. Cosign creates a key pair with public and private keys and then uses the private key to create a digital signature of software artifacts, that is, any item produced during the software development lifecycle such as containers or open source software packages.

Fulcio is a certificate authority that binds public keys to emails (such as a Google account) using OpenID Connect, essentially notarizing a short-lived key pair against a particular login. A certificate authority issues digital certificates that certify that a particular public key is owned by a particular entity. The certificate authority therefore serves as a trusted third party, helping parties that need to attest and verify identities. By connecting their identity to a verified email or other unique identifier, Fulcio enables software developers to confirm certain credentials associated with themselves. Developers can attest that they truly did create their signed artifacts and later software consumers can then verify that the software artifacts they use really did come from the expected software developers.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Define a certificate and a certificate authority.

- Define OpenID Connect (OIDC) tokens.

- Create and examine a Fulcio certificate.

- Understand how Fulcio issues certificates.

- Explain the purpose and contributions of Fulcio.

Certificates

A certificate is a signed document that associates a public key with an identity such as an email address. The term “document” refers to a file or any electronic representation of a paper document. That the document must be signed implies that some party uses a digital signature to certify the document. You could think of a certificate as the digital equivalent of a passport: a document from a trusted authority that links information to an identity.

Fulcio issues X.509 certificates. X.509 certificates are an International Telecommunication Union (ITU) standard that defines the format of public keys, and they are commonly used in many internet protocols, such as those that enable HTTPS. These certificates are what bind a given identity to a public key by using a digital signature.

Below is an example of an X.509 certificate used to authenticate a secure website connection.

Example of X.509 Certificate

Certificate Authority

You rely on certificate authorities every time you open a browser and make a connection to a website. These certificate authorities, such as Let’s Encrypt, sign certificates that link a particular domain with a particular public key, allowing users to use HTTPS securely, knowing that a malicious third party is not pretending to be the real website. When a user visits a website, the user’s browser checks that a certificate authority trusted by the browser vouches for that certificate.

As a certificate authority, Fulcio operates analogously to the certificate authorities that are responsible for web encryption. Fulcio does not, however, tie website domains to public keys. Instead, Fulcio creates and signs certificates that bind together email addresses and public keys. Binding an email address and public key are critical to how Sigstore works. Software developers want to attest that they were indeed responsible for publishing a particular software artifact. Fulcio lets these developers issue claims associated with their public identity. As a result, software consumers can later check the end-to-end integrity of the software artifacts they consume and know that this artifact was indeed created by the party that claims to have produced that artifact.

To return to the digital passport metaphor, each national government, the entities that issue passports, is equivalent to a certificate authority.

Fulcio Certificate Authority

OpenID Connect (OIDC) Tokens

OpenID Connect (or OIDC) is a protocol that enables authentication without the service provider having to store and manage passwords. Authentication refers to establishing that the person operating an application or using a browser is who they claim to be. Allowing the service, like Sigstore, to rely on OIDC means that the service transfers responsibility for creating and managing passwords to other OIDC providers like GitHub, Google, and Microsoft, solving the key management issues that many online service providers prefer to avoid.

The use of the OIDC protocol by Sigstore means that a user can rely on workflows they are already familiar with, such as logging into Google, in order to prove their identity. The OIDC “provider” (Google in this example) then vouches on the user’s behalf to Fulcio that the user is who they say they are.

Returning again to the digital passport metaphor, the OIDC protocol is similar to how a passport can be used at an airport to prove your identity. The airport did not issue the passport (that is, the certificate) but it trusts the proof provided via the certificate.

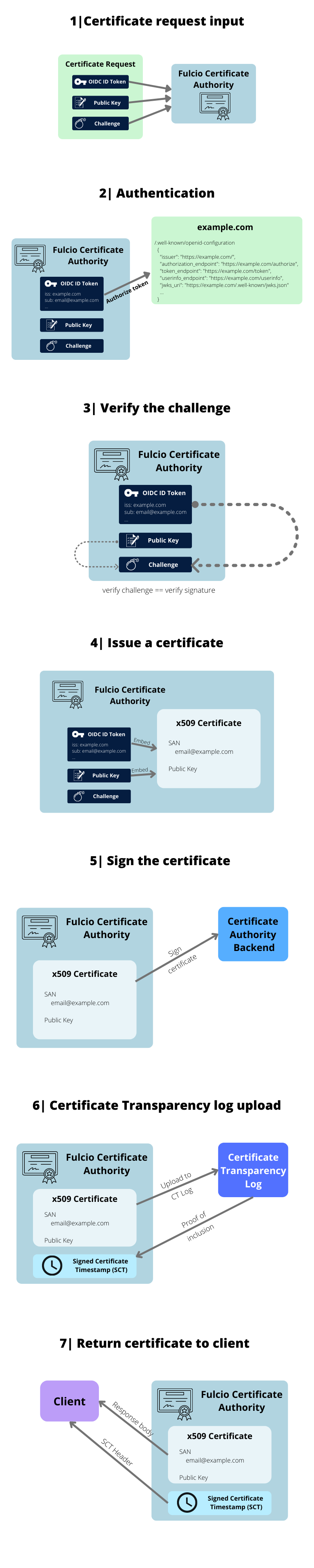

How Fulcio Issues Certificates

The user initiates a login to Fulcio using an OIDC provider such as GitHub, Google, or Microsoft. The user and an OIDC provider (for instance, GitHub) then engage in the OIDC protocol where the user logs in to GitHub to prove their identity. The OIDC provider, if the login is successful, returns an “access token,” which proves to Fulcio that the user controls the email address they claim to control. Fulcio then creates a certificate and timestamps it, returning the timestamp to the user and placing the certificate in the Rekor transparency log too.

The process described above, in reality, can be decomposed into even more steps. For a full understanding with helpful diagrams, consult the Fulcio documentation.

The Purpose and Contributions of Fulcio

The main task of Fulcio is to link public keys to email addresses. The detailed explanation earlier simply elaborates on how Fulcio binds public keys to email addresses.

Why bind public keys to email addresses? Because third parties want to verify that an artifact was signed by the person who claimed they signed the artifact. Fulcio acts as a trusted party that vouches on behalf of its users that a certain user proved their identity at a certain time.

This timestamping is an essential part of the process. The timestamp proves that the signing happened at a particular time and it creates a short time window (about 20 minutes) for the user to sign the artifact that they are signing. A verifying party then needs to check that the artifact they are verifying was not only signed by the party that claims to have signed the artifact, but also that it was done within a valid time window.

Lab

In this lab, we are going to create and examine a Fulcio certificate to demonstrate how Fulcio can work in practice. To follow along, you will need to have Cosign installed on your local system. If you haven’t installed Cosign yet, you can follow the instructions described in the Cosign chapter of this course, or you can follow one of the installation methods described in the official documentation.

Generating a Fulcio Certificate

To get started, set the COSIGN_EXPERIMENTAL variable to 1. This is required in order to enable the keyless signing flow functionality, which is currently in beta.

$ export COSIGN_EXPERIMENTAL=1

Next, place some text in a text file. For instance:

$ echo "test tile contents" > test-file.txt

Next, let’s generate a key pair with Cosign. Enter a password twice after running the command below. For users that have not yet installed Cosign, Cosign installation instructions are here. Using Cosign requires Go v1.16 or higher. Go provides official download instructions.

Then use Cosign to sign this test-file.txt, outputting a Fulcio certificate named “fulcio.crt.base64”. The sign-blob subcommand allows Cosign to sign a blob. This command will open a browser tab and will require you to sign in through one of the OIDC providers: GitHub, Google, or Microsoft. This step represents the user proving their identity.

$ cosign sign-blob test-file.txt --output-certificate

fulcio.crt.base64 --output-signature fulcio.sig

After authentication, you can close the browser tab. In your terminal, you should see output similar to this:

Using payload from: test-file.txt

Generating ephemeral keys...

Retrieving signed certificate...

Your browser will now be opened to: https://oauth2.sigstore.dev/auth/auth?access_type=online&client_id=sigstore&code_challenge=...

Successfully verified SCT...

using ephemeral certificate:

-----BEGIN CERTIFICATE-----

(...)

-----END CERTIFICATE-----

tlog entry created with index: 2494952

Signature wrote in the file fulcio.sig

Certificate wrote in the file fulcio.crt.base64

The output indicates that Sigstore is using ephemeral keys to generate a certificate for test-file.txt. The certificate, which we’ll verify in the next section, is saved to a file named fulcio.crt.base64.

Inspecting and Verifying Fulcio Certificates

To inspect the certificate generated in the previous section of this chapter, we will first decode it with the base64 command line tool, which is used for encoding and decoding binary to text. Base64 is widely used on the world wide web for binary-to-text encoding. Then we will use a third-party tool called step to actually inspect the decoded certificate.

$ base64 -d < fulcio.crt.base64 > fulcio.crt

To install step, which is a tool related to public key infrastructure workflows, follow the instructions from their official documentation.

Then, inspect the certificate using step’s inspect command.

$ step certificate inspect fulcio.crt

A sample output is below. Pay attention, especially to the x509v3 Subject Alternative Name field, which is the email associated with the party that created the signature and the issuer, which is Sigstore. The ten minute time window of validity also details the period of time for which the signature is valid.

Certificate:

Data:

Version: 3 (0x2)

Serial Number: 445971695346061852979091305347141417164194935 (0x13ff8105719cba6ad0caa5ce9f34603ce9c477)

Signature Algorithm: ECDSA-SHA384

Issuer: O=Sigstore.dev,CN=sigstore

Validity

Not Before: Mar 24 20:14:37 2022 UTC

Not After : Mar 24 20:24:36 2022 UTC

Subject:

Subject Public Key Info:

Public Key Algorithm: ECDSA

Public-Key: (256 bit)

X:

4b:fc:7d:9c:4a:56:30:75:67:fd:d6:1f:a6:f3:05:

04:ff:c8:ab:c6:2c:5f:ea:59:f9:ed:07:fa:c2:ae:

04:19

Y:

15:44:38:f3:77:87:63:91:0c:08:b6:4f:ca:67:36:

3f:38:dc:fc:bc:07:5c:8f:ec:d3:b2:31:66:a8:3d:

fa:98

Curve: P-256

X509v3 extensions:

X509v3 Key Usage: critical

Digital Signature

X509v3 Extended Key Usage:

Code Signing

X509v3 Basic Constraints: critical

CA:FALSE

X509v3 Subject Key Identifier:

5A:F0:DE:DA:CF:D0:73:F1:5A:88:B2:9F:8E:03:5F:51:6E:8C:57:19

X509v3 Authority Key Identifier:

keyid:58:C0:1E:5F:91:45:A5:66:A9:7A:CC:90:A1:93:22:D0:2A:C5:C5:FA

X509v3 Subject Alternative Name: critical

email:[email protected]

1.3.6.1.4.1.57264.1.1:

https://github.com/login/oauth

Signature Algorithm: ECDSA-SHA384

30:65:02:31:00:98:00:17:7a:98:f2:d4:89:05:d2:7a:91:93:

73:92:e6:3f:9d:69:a5:7c:28:9f:60:72:29:e3:b7:d3:5e:2f:

1a:00:35:99:4f:92:da:02:cd:ec:83:49:f3:27:3a:39:21:02:

30:04:a6:0c:42:a4:38:d9:ac:da:8f:b5:2f:4c:f5:ad:4b:d4:

c6:7d:8b:43:46:91:c1:9d:80:43:44:a9:26:26:26:0f:cf:e2:

ab:aa:ef:6d:ec:1c:28:de:d3:ac:aa:fd:1b

We will then verify the certificate against the Fulcio certificate authority root, by using step certificate verify to execute the certificate path validation algorithm for x.509 certificates.

$ step certificate verify fulcio.crt --roots

~/.sigstore/root/targets/fulcio_v1.crt.pem

The final command checks the signature in the fulcio.sig file, tracing the certificate up to the Fulcio root certificate.

$ cosign verify-blob test-file.txt --signature fulcio.sig --cert fulcio.crt.base64

You will receive output following this command.

tlog entry verified with uuid: 727e2834d2af9389bbc49ebd798050a72698fec4fabff1433cd83071b4a6914d index: 2494952

Verified OK

You should get a Verified OK message along with the UUID and index number of the certificate within Fulcio.

Further Reading Resources

X.509 Certificates

International Telecommunication Union (ITU)

Let’s Encrypt

OpenID Connect (OIDC)

Fulcio documentation

Cosign installation instructions

Go download instructions

Step install instructions

Dan Lorenc, “A Fulcio Deep Dive,” Chainguard Blog, November 12, 2021

FAQ about Certificates, U.S. Government Chief Information Office

“Certificate Issuing Overview,” Fulcio GitHub documentation (March 29, 2022)

Chapter 4. Rekor: Software Supply Chain Transparency Log

Overview

Previous chapters explained how the components of sigstore allow users to authenticate artifacts against identities. Cosign creates a public/private key-pair and then uses that private key to create a digital signature of software artifacts such as containers or open source software packages. Fulcio is a certificate authority that binds public keys to emails using Open ID Connect tokens, essentially notarizing a particular login with a short-lived key pair.

Rekor, the subject of this chapter, stores records of artifact metadata, providing transparency for signatures and therefore helping the open source software community monitor and detect any tampering of the software supply chain. On a technical level, it is an append-only (sometimes called “immutable”) data log that stores signed metadata about a software artifact, allowing software consumers to verify that a software artifact is what it claims to be. You could think of Rekor as a bulletin board where anyone can post and the posts cannot be removed, but it’s up to the viewer to make informed judgments about what to believe.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Define a transparency log.

- Explain how Rekor fits into software supply chain security.

- Install rekor-cli.

- Query Rekor.

- Describe the data one can receive by querying Rekor.

Transparency Log

Rekor’s role as a transparency log is the source of its security benefits for the software supply chain. Because the Rekor log is tamper-evident — meaning that any tampering can be detected — malicious parties will be less likely to tamper with the software artifacts protected by sigstore.

In order to detect tampering, we can use monitors — software that examines the Rekor log and searches for anomalies — to verify that nothing has been manipulated outside of standard practices. Additionally, downstream users can search Rekor for signatures associated with signed artifact metadata, can verify the signature, and can make an informed judgment about what security guarantees to trust about a signed artifact.

The Fulcio certificate authority enables a downstream user to trust that a public key associated with a particular artifact metadata entry from Rekor is associated with a particular identity, and Cosign performs this verification with a single convenient command.

Public Instance of Rekor

A public instance of Rekor is run as a non-profit, public good transparency service that the open source software community can use. The service lives at https://rekor.sigstore.dev/. Those who are interested in helping to operate or maintain the Rekor public instance, or those who would like to discuss a production use case of the public instance can reach out via the mailing list.

The latest Signed Tree hashes of Rekor are published on Google Cloud Storage. These are stored in both unverified raw and verified decoded formats; the signatures can be verified by users against Rekor’s public key. Entries include a short representation of the state of Rekor, which is posted to GCS, and can be verified by users against Rekor’s public key. These representations can be used to check that a given entry was in the log at a given time.

Rekor Usage

Rekor provides a restful API based server for validation and a transparency log for storage, accessible via a command-line interface (CLI) application: rekor-cli. You can install rekor-cli with Go, which we will discuss in the lab section below. Alternatively, you can navigate to the Rekor release page to grab the most recent release, or you can build the Rekor CLI manually.

Through the CLI, you can make and verify entries, query the transparency log to prove the inclusion of an artifact, verify the integrity of the transparency log, or retrieve entries by either public key or artifact.

To access the data stored in Rekor, the rekor-cli requires either the log index of an entry or the universally unique identifier (UUID) of an artifact.

The log index of an entry identifies the order in which the entry was entered into the log. Someone who wants to collect all the log entries or perhaps a large subset of the entries might use the log index, and receive an object as below, in their standard output.

LogID:

c0d23d6ad406973f9559f3ba2d1ca01f84147d8ffc5b8445c224f98b9591801d

Index: 100

IntegratedTime: 2021-01-19T19:38:52Z

UUID: 2343d145e62b1051b6a2a54582b69a821b13f31054539660a020963bac0b33dc

Body: {

"RekordObj": {

"data": {

"hash": {

"algorithm": "sha256",

"value":

"bf9f7899c65cc4decf96658762c84015878e5e2e41171bdb39e6ac39b4d6b797"

}

},

"signature": {

"content": "LS0tL…S0=",

"format": "pgp",

"publicKey": {

"content": "LS…0tLS0="

}

}

}

}

The RekordObj is indicated inside the body field, and is one of the standard formats used by Rekor to indicate a digital signature of an object. The signature in this entry was generated via PGP, a traditional method of creating digital signatures, sometimes also used to sign code artifacts. Many other digital signature types are accepted. The signature block contains content fields that are base64-encoded, a form of encoding that enables reliably sending binary data over networks.

There are a number of different formats stored in the Rekor log, each associated with a particular type of artifact and use case.

Users of Rekor also have an offline method for determining whether a particular entry exists in a Rekor log by leveraging inclusion proofs, which are enabled through Merkle trees. Merkle trees are a data structure that enables a party to use cryptographic hash functions — a way of mapping potentially large values to relatively short digests — to prove that a piece of data is contained within a much larger data structure. This proof is accomplished by providing a series of hashes to the user, hashes that if recombined prove to the user that an entry is indeed in the Rekor log. Sigstore users can “staple” such an inclusion proof to an artifact, attaching the inclusion proof next to an artifact in a repository, and therefore proving that the artifact is indeed included in Rekor. For a detailed description of Merkle trees and inclusion proofs, refer to the “further reading resources” section at the end of chapter 5.

Setting Up an Internal Rekor Instance

Your organization can also set up its own instance of Rekor, or you can individually set up a Rekor server to more fully understand it. You can deploy the Rekor server through Project Sigstore’s Docker Compose file, through a Kubernetes operator, with a Helm chart, or you can build a Rekor server yourself.

In order to build a Rekor server, you will need Go, a MySQL-compatible database, and you will need to build Trillian, an append-only log. In the lab section, we will walk through how to set up a Rekor server locally.

Lab

In this lab you’ll have a practical overview of how to install rekor-cli and how to use Rekor, covering its main commands and features.

Rekor Installation

To install the Rekor command line interface (rekor-cli) with Go, you will need Go version 1.16 or greater. For Go installation instructions, see the official Go documentation. If you have Go installed already, you can check your Go version via this command.

$ go version

go version go1.13.8 linux/amd64

You will also need to set your $GOPATH, the location of your Go workspace.

$ export GOPATH=$(go env GOPATH)

You can then install rekor-cli:

$ go install -v github.com/sigstore/rekor/cmd/rekor-cli@latest

Check that the installation of rekor-cli was successful using the following command:

$ rekor-cli version

You should receive an output similar to that below:

GitVersion: v0.4.0-59-g2025bf8

GitCommit: 2025bf8aa50b368fc3972bb276dfeae8b604d435

GitTreeState: clean

BuildDate: '2022-01-26T00:20:33Z'

GoVersion: go1.17.6

Compiler: gc

Platform: darwin/arm64

Now that you have the Rekor CLI tool successfully installed, you can start working with it.

Querying Rekor

In order for us to access the data stored in Rekor, the rekor-cli requires either the log index of an entry or the UUID of a software artifact.

For instance, to retrieve entry number 100 from the public log, use this command:

$ rekor-cli get --rekor_server https://rekor.sigstore.dev --log- index 100

An abridged version of the output is below:

LogID: c0d23d6ad406973f9559f3ba2d1ca01f84147d8ffc5b8445c224f98b9591801d

Index: 100

IntegratedTime: 2021-01-19T19:38:52Z

UUID: 2343d145e62b1051b6a2a54582b69a821b13f31054539660a020963bac0b33dc

Body: {

"RekordObj": {

"data": {

"hash": {

"algorithm": "sha256",

"value": "bf9f7899c65cc4decf96658762c84015878e5e2e41171bdb39e6ac39b4d6b797"

}

},

"signature": {

"content": "LS0tL…S0=",

"format": "pgp",

"publicKey": {

"content": "LS…0tLS0="

}

}

}

}

The next command will produce the same output but uses the UUID to retrieve the artifact:

$ rekor-cli get --uuid

2343d145e62b1051b6a2a54582b69a821b13f31054539660a020963bac0b33dc

It is also possible to use a web API to return results that are similar to those above. For instance, we can use curl to fetch the same artifact by its UUID with the following query:

$ curl -X GET "https://rekor.sigstore.dev/api/v1/log/entries/2343d145e62b1051b6a2a54 582b69a821b13f31054539660a020963bac0b33dc"

By appending the UUID value returned by the rekor-cli get command that we ran before, we can obtain detailed information about a specific artifact that has been previously registered within the Rekor public instance.

Signing and Uploading Metadata with rekor-cli

For this example, we will use SSH to sign a text document. SSH is often used to communicate securely over an unsecured network and can also be used to generate public and private keys appropriate for signing an artifact.

First, generate a key pair. This command will generate a public key and a private key file. You’ll be able to easily identify the public key because it uses the .pub extension.

$ ssh-keygen -t ed25519 -f id_ed25519

Then, create a text file called README.txt with your favorite text editor. You can enter as little or as much text in that file as you would like.

For example, we can use nano:

$ nano README.txt

Then within the file, we can type some text into it, such as the following.

[label README.txt]

Hello, Rekor!

Save and close the file.

Next, sign this file with the following command. This command produces a signature file ending in the .sig extension.

$ ssh-keygen -Y sign -n file -f id_ed25519 README.txt

You should receive the following output.

Signing file README.txt

Write signature to README.txt.sig

Then, upload this artifact to the public instance of the Rekor log.

$ rekor-cli upload --artifact README.txt --signature README.txt.sig -- pki-format=ssh --public-key=id_ed25519.pub

The returned value will include a string similar to:

https://rekor.sigstore.dev/api/v1/log/entries/83140d699ebc33dc84b702d2 f95b209dc71f47a3dce5cce19a197a401852ee97

Save the UUID returned after using this command. In this example, the UUID is 83140d699ebc33dc84b702d2f95b209dc71f47a3dce5cce19a197a401852ee97.

Now you can query Rekor for your recently saved entry. Run the following command, replacing UUID with the UUID number obtained in the previous command.

$ rekor-cli get --uuid UUID

Once you receive output formatted as a JSON with details on the signature, you will know you have successfully stored a signed metadata entry in Rekor.

Install Your Own Rekor Instance Locally (Optional)

While individual developers may not generally need to set up their own instance of Rekor, it may be worthwhile to set up your own local instance in order to further understand how Rekor works under the hood.

Create and Run a Database Backend

To start, we’ll need to create a database backend; while sigstore accepts several different databases, we’ll work with MariaDB here, so make sure you have it installed.

If you are on Debian or Ubuntu, you can install it with the following command.

$ sudo apt install -y mariadb-server

If you are on macOS, you can install it with Homebrew. If you don’t already have Homebrew installed, visit brew.sh to set it up.

$ brew install mariadb

If you’re using another operating system, review the official MariaDB installation documentation.

With MariaDB installed, start the database.

For Debian or Ubuntu, you can run:

$ sudo mysql_secure_installation

For macOS, you can run:

$ brew services start mariadb && sudo mysql_secure_installation

Once you run the above command, you will receive a number of prompts as terminal output. You can answer “no” or N to the first question on changing the root password, and “yes” or Y to the remaining prompts.

Change the root password? [Y/n] n

…

Remove anonymous users? [Y/n] Y

…

Disallow root login remotely? [Y/n] Y

…

Remove test database and access to it? [Y/n] Y

…

Thanks for using MariaDB!

Once you receive the Thanks for using MariaDB! output, you’re ready to create your database. Change into your rekor/scripts directory:

$ cd $HOME/src/rekor/scripts

From this directory, you can run the database creation script.

$ sudo sh -x createdb.sh

At this point, we are ready to move on to installing Trillian.

Install and Set Up Trillian

Trillian offers a transparent, append-only, and cryptographically verifiable data store. Trillian will store its records in the MariaDB database we just created. We can install Trillian with Go.

$ go install github.com/google/trillian/cmd/trillian_log_server@latest

$ go install github.com/google/trillian/cmd/trillian_log_signer@latest

$ go install github.com/google/trillian/cmd/createtree@latest

We’ll start the Trillian log server, providing the API used by Rekor and the Certificate Transparency frontend.

$ $HOME/go/bin/trillian_log_server --logtostderr \

-http_endpoint=localhost:8090 - rpc_endpoint=localhost:8091

Next, let’s start the log signer which will sequence data into cryptographically verifiable Merkle trees and periodically check the database.

$ $HOME/go/bin/trillian_log_signer \